Why Sort is row-based in Velox — A Quantitative Assessment

TL;DR

Velox is a fully vectorized execution engine[1]. Its internal columnar memory layout enhances cache locality, exposes more inter-instruction parallelism to CPUs, and enables the use of SIMD instructions, significantly accelerating large-scale query processing.

However, some operators in Velox utilize a hybrid layout, where datasets can be temporarily converted

to a row-oriented format. The OrderBy operator is one example, where our implementation first

materializes the input vectors into rows, containing both sort keys and payload columns, sorts them, and

converts the rows back to vectors.

In this article, we explain the rationale behind this design decision and provide experimental evidence for its implementation. We show a prototype of a hybrid sorting strategy that materializes only the sort-key columns, reducing the overhead of materializing payload columns. Contrary to expectations, the end-to-end performance did not improve—in fact, it was even up to 3× slower. We present the two variants and discuss why one is counter-intuitively faster than the other.

Row-based vs. Non-Materialized

Row-based Sort

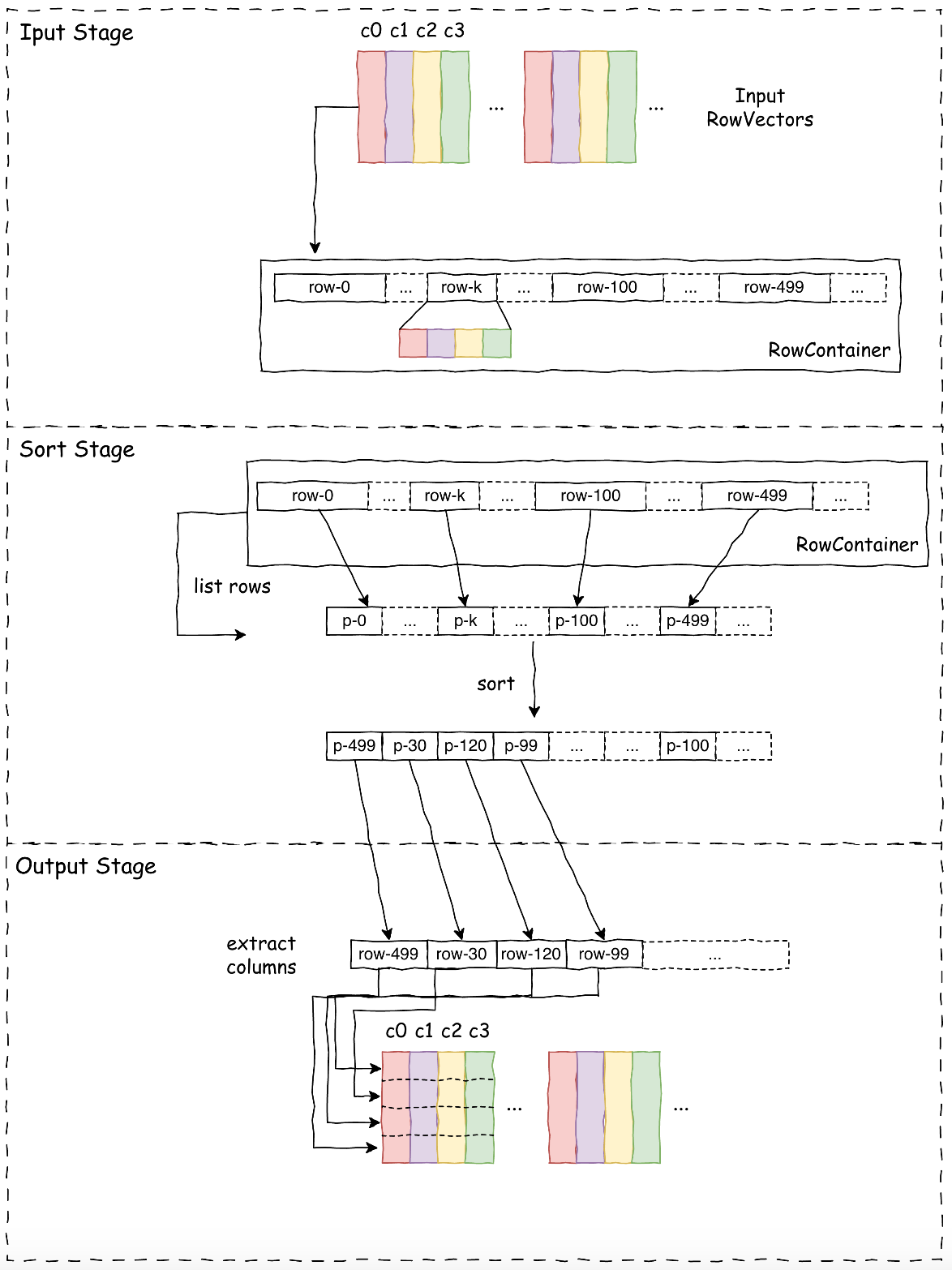

The OrderBy operator in Velox’s current implementation uses a utility called SortBuffer to perform

the sorting, which consists of three stages:

- Input Stage: Serializes input Columnar Vectors into a row format, stored in a RowContainer.

- Sort Stage: Sorts based on keys within the RowContainer.

- Output Stage: Extract output vectors column by column from the RowContainer in sorted order.

While row-based sorting is more efficient than column-based sorting[2,3], what if we only materialize the sort key columns? We could then use the resulting sort indices to gather the payload data into the output vectors directly. This would save the cost of converting the payload columns to rows and back again. More importantly, it would allow us to spill the original vectors directly to disk rather than first converting rows back into vectors for spilling.

Non-Materialized Sort

We have implemented a non-materializing sort strategy designed

to improve sorting performance. The approach materializes only the sort key columns and their original vector indices,

which are then used to gather the corresponding rows from the original input vectors into the output vector after the

sort completes. It changes the SortBuffer to NonMaterizedSortBuffer, which consists of three stages:

- Input Stage: Holds the input vector (its shared pointer) in a list, serializes key columns and additional index columns (VectorIndex and RowIndex) into rows, stored in a RowContainer.

- Sort Stage: Sorts based on keys within the RowContainer.

- Output Stage: Extracts the VectorIndex and RowIndex columns, uses them together to gather the corresponding rows from the original input vectors into the output vector.

In theory, this should have significantly reduced the overhead of materializing payload columns, especially for wide tables, since only sorting keys are materialized. However, the benchmark results were the exact opposite of our expectations. Despite successfully eliminating expensive serialization overhead and reducing the total instruction the end-to-end performance was 3x times slower.

Benchmark Result

To validate the effectiveness of our new strategy, we designed a benchmark with a varying number of payload columns:

- Inputs: 1000 Input Vectors, 4096 rows per vector.

- Number of payload columns: 64, 128, 256.

- L2 cache: 80 MiB, L3 cache: 108 MiB.

| numPayloadColumns | Mode | Input Time | Sorting Time | Output Time | Total Time | Desc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | Row-based | 4.27s | 0.79s | 4.23s | 11.64s | Row-based is 3.9x faster |

| Columnar | 0.28s | 0.84s | 42.30s | 45.90s | ||

| 128 | Row-based | 20.25s | 1.11s | 5.49s | 31.43s | Row-based is 2.0x faster |

| Columnar | 0.27s | 0.51s | 59.15s | 64.20s | ||

| 256 | Rows-based | 29.34s | 1.02s | 12.85s | 51.48s | Row-based is 3.0x faster |

| Columnar | 0.87s | 1.10s | 144.00s | 154.80s |

The benchmark results confirm that Row-based Sort is the superior strategy, delivering a 1.9x to 3.9x overall speedup compared to Columnar Sort. While Row-based Sort incurs a significantly higher upfront cost during the Input phase (peaking at 104s), it maintains a highly stable and efficient Output phase (maximum 32s). In contrast, Columnar Sort suffers from severe performance degradation in the Output phase as the payload increases, with execution times surging from 42s to 283s, resulting in a much slower total execution time despite its negligible input overhead.

To identify the root cause of the performance divergence, we utilized perf stat to analyze

micro-architectural efficiency and perf mem to profile memory access patterns during the critical

Output phase.

| Metrics | Row-based | Columnar | Desc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Instructions | 555.6 Billion | 475.6 Billion | Row +17% |

| IPC (Instructions Per Cycle) | 2.4 | 0.82 | Row 2.9x Higher |

| LLC Load Misses (Last Level Cache) | 0.14 Billion | 5.01 Billion | Columnar 35x Higher |

| Memory Level | Row-based Output | Columnar Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| RAM Hit | 5.8% | 38.1% |

| LFB Hit | 1.7% | 18.9% |

| RAM Hit | 5.8% | 38.1% |

The results reveal a stark contrast in CPU utilization. Although the Row-based approach executes 17% more instructions (due to serialization overhead), it maintains a high IPC of 2.4, indicating a fully utilized pipeline. In contrast, the Columnar approach suffers from a low IPC of 0.82, meaning the CPU is stalled for the majority of cycles. This is directly driven by the 35x difference in LLC Load Misses, which forces the Columnar implementation to fetch data from main memory repeatedly. The memory profile further confirms this bottleneck: Columnar mode is severely latency-bound, spending 38.1% of its execution time waiting for DRAM (RAM Hit) and experiencing significant congestion in the Line Fill Buffer (18.9% LFB Hit), while Row-based mode effectively utilizes the cache hierarchy.

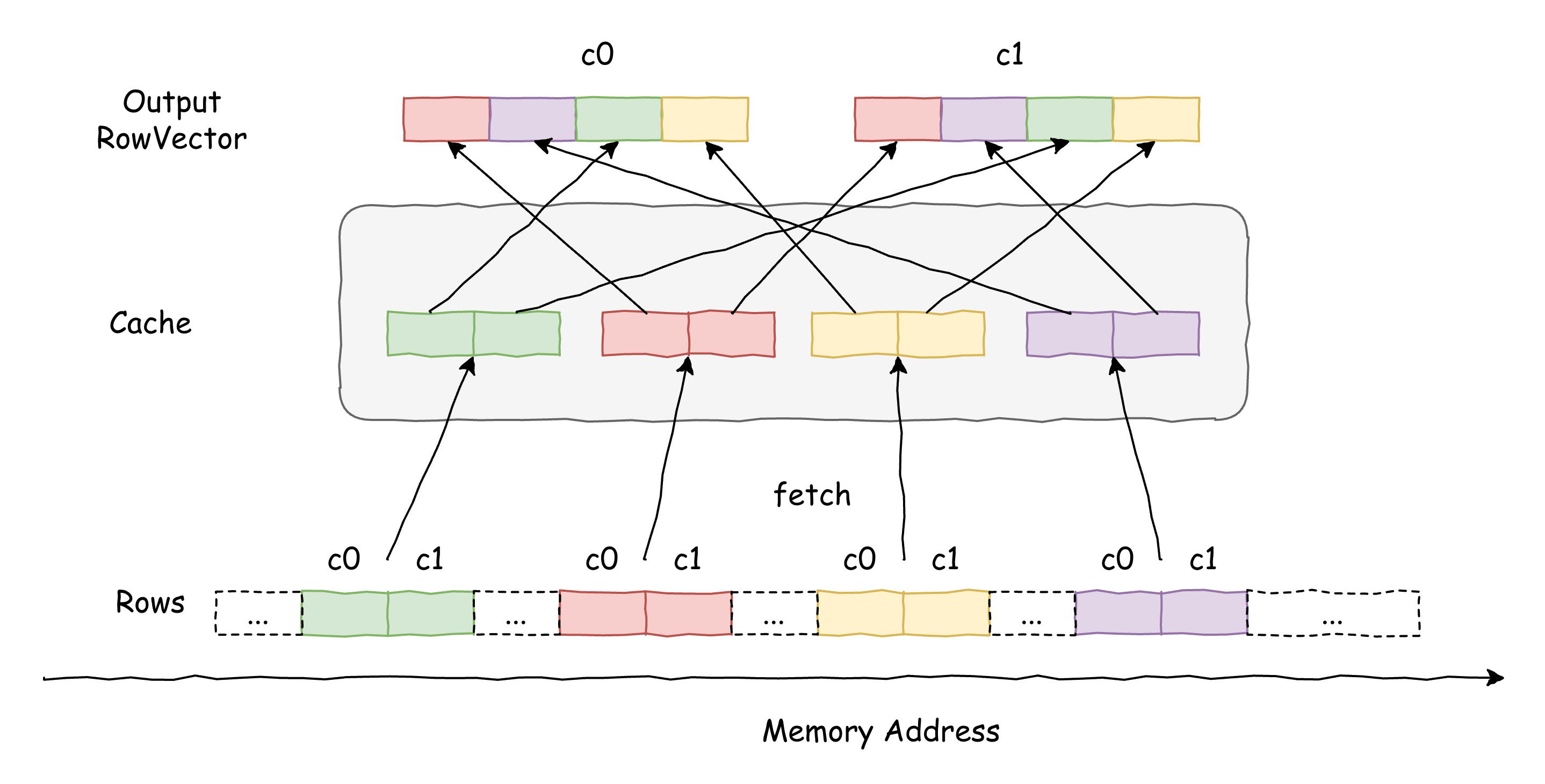

The Memory Access Pattern

Why does the non-materializing sort, specifically its gather method, cause so many cache misses? The answer lies in its memory access pattern. Since Velox is a columnar engine, the output is constructed column by column. For each column in an output vector, the gather process does the following:

- It iterates through all rows of the current output vector.

- For each row, locate the corresponding input vector via the sorted vector index.

- Locates the source row in the corresponding input vector.

- Copies the data from that single source cell to the target cell.

The sorted indices, by nature, offer low predictability. This forces the gather operation for a single output column to jump unpredictably across as many as different input vectors, fetching just one value from each. This random access pattern has two devastating consequences for performance.

First, at the micro-level, every single data read becomes a "long-distance" memory jump. The CPU's hardware prefetcher is rendered completely ineffective by this chaotic access pattern, resulting in almost every lookup yielding a cache miss.

Second, at the macro-level, the problem compounds with each column processed. The sheer volume of data touched potentially exceeds the size of the L3 cache. This ensures that by the time we start processing the next payload column, the necessary vectors have already been evicted from the cache. Consequently, the gather process must re-fetch the same vector metadata and data from main memory over and over again for each of the 256 payload columns. This results in 256 passes of cache-thrashing, random memory access, leading to a catastrophic number of cache misses and explaining the severe performance degradation.

In contrast, Velox’s current row-based approach serializes all input vectors into rows, with each allocation producing a contiguous buffer that holds a subset of those rows. Despite the serialization, the row layout preserves strong locality when materializing output vectors: once rows are in the cache, they can be used to extract multiple output columns. This leads to much better cache-line utilization and fewer cache misses than a columnar layout, where each fetched line often yields only a single value per column. Moreover, the largely sequential scans over contiguous buffers let the hardware prefetcher operate effectively, boosting throughput even in the presence of serialization overhead.

Conclusion

This study reinforces the core principle of performance engineering: Hardware Sympathy. Without understanding the characteristics of the memory hierarchy and optimizing for it, simply reducing the instruction count usually does not guarantee better performance.